I’ve been meditating on the Gospel reading from last Sunday. Help from the blogosphere has let me far deeper into it than before.

My starting point was the meditation from Scott Hahn. He publishes these on Wednesday each week, and I find them a great way to prepare for the next Sunday’s Mass. This time, Hahn pointed up the correlation between the temptations of Israel in the desert (each of which they fell into) and the temptations of Christ.

In today’s epic Gospel scene, Jesus relives in His flesh the history of Israel.

We’ve already seen that like Israel, Jesus has passed through water, been called God’s beloved Son (see Luke 3:22; Exodus 4:22). Now, as Israel was tested for forty years in the wilderness, Jesus is led into the desert to be tested for forty days and nights (see Exodus 15:25).

He faces the temptations put to Israel: Hungry, He’s tempted to grumble against God for food (see Exodus 16:1-13). As Israel quarreled at Massah, He’s tempted to doubt God’s care (see Exodus 17:1-6). When the Devil asks His homage, He’s tempted to do what Israel did in creating the golden calf (see Exodus 32).

Jesus fights the Devil with the Word of God, three times quoting from Moses’ lecture about the lessons Israel was supposed to learn from its wilderness wanderings (see Deuteronomy 8:3; 6:16; 6:12-15).

Hahn goes on to explain why these readings are used to begin our Lent.

Since Sunday, I’ve found several other commentaries on the same readings. The Holy Father, in his Sunday Angelus, said:

At the beginning of his public ministry Jesus had to unmask and reject the false images of the Messiah that the tempter proposed to him. But these temptations are also false images of man, which always harass our conscience, disguising themselves as suitable, effective and even good proposals. The evangelists Matthew and Luke present 3 temptations of Jesus, differing in part only in the order. The nucleus of these temptations always consists in instrumentalizing God for our own interests, giving more importance to success or to material goods. The tempter is clever: he does not direct us immediately towar evil but toward a false good, making us believe that power and things that satiate primary needs are what is most real. In this manner God becomes secondary; he is reduced to a means, he becomes unreal, he no longer counts, he disappears. In the final analysis, faith is what is at stake in temptations because God is at stake. In the decisive moments of life and, in fact, in every moment of life, we are faced with a choice: do we want to follow the “I” or God? Do we want to follow individual interest or rather the true Good, that which is really good?

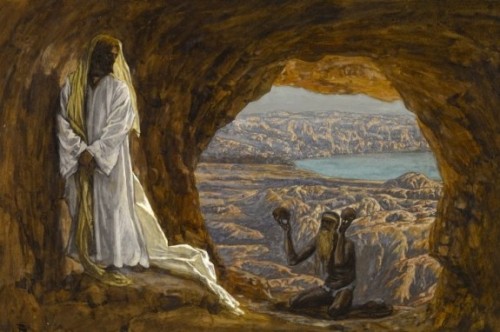

Deacon Greg Kandra posted the image I’ve used above, and talks about the artist’s interpretation – that Satan came in the guise of a hungry man looking for bread.

Tissot is upping the ante here, significantly. It is one thing for Christ to deny himself bread. How can he deny the poor? How can he see this desperate man and not want to help? The devil is clearly not just going after Christ’s hunger, but also his heart—a heart that burns with love for the poor, the outcast, the neglected. It’s a brilliant choice by Tissot, I think, and dramatically raises the stakes. It demonstrates just how painful those days in the desert must have been. It underscores that the encounter with the Evil One was about more than craving bread. Satan went even deeper.

The Happy Priest points out that temptation comes from two sources: our fallen nature and Satan:

Temptation will always be a part of our lives. No matter our age or the circumstances of our lives, temptation will be something that we have to deal with until the end of our journey here on earth.

Not every temptation is caused by Satan, so we need to look at the two causes of temptation.

Most temptations are caused by our fallen human nature. As we saw last Sunday, Original Sin has wounded our human nature. We simply do not have complete control over our mind, memory, imagination, will, passions and emotions. We will always struggle with something.

Our Lenten disciplines, says the Happy Priest, are part of our lifelong training to control our fallen nature:

A Christian magazine once surveyed their subscribers regarding the areas of their greatest spiritual challenges. The results showed that their greatest temptation was materialism. After materialism, followed pride, self-centeredness, laziness, anger, lust, envy, gluttony and finally lying.

The survey respondents noted temptations were frequent and more forceful when they had neglected their time with God and when they were physically tired. They stated that the ability to resist temptation was made easier by a strong spiritual life, avoiding compromising situations and being accountable to someone.

As I struggle hourly with the temptation to slip my Lenten fast – I’ve given up (other people’s) fiction for Lent – I need to remember that, as Fr Duffy says:

Lent isn’t easy. It isn’t fun. It’s not supposed to be. Nothing that changes us is easy. And that’s what Lent is all about isn’t it. That’s why we fast. Right? To make us reflect on our lives and to challenge us to grow deeper in love with the Lord Jesus. Fasting helps us to become more attune to the other…

Someone said on Facebook this morning: “we don’t fast so that God will hear us, rather we fast so that we will be able to hear God”. A seminarian texted me on Ash Wednesday and said that It seems like it’s only on Ash Wednesday and Fridays during lent that we crave a porterhouse steak. That’s the human condition – we crave what we can’t have. Take those cravings as reminders to pray. Take those moments of desire and use them to know yourself a little better. Become more human this Lent. Become a Saint. Be what you and I are meant to be. Make of your life a gift to God.